by Howard Rheingold, originally published in The Atlantic (July 2012)

Howard Rheingold is the author of many books on social media and how it shapes society, including Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology, The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier, and most recently, Net Smart: How to Thrive Online. A key early member of the most influential early online community remembers the site, which is now up for sale.

In the late 1980s, decades before the term "social media" existed, in a now legendary and miraculously still living virtual community called "The WELL," a fellow who used the handle "Philcat" logged in one night in a panic: his son Gabe had been diagnosed with leukemia, and in the middle of the night he had nowhere else to turn but the friends he knew primarily by the text we typed to each other via primitive personal computers and slow modems.

By the next morning, an online support group had coalesced, including an MD, an RN, a leukemia survivor, and several dozen concerned parents and friends. Over the next couple years, we contributed over $15,000 to Philcat and his family. We'd hardly seen each other in person until we met in the last two pews of Gabe's memorial service.

Flash forward nearly three decades. I have not been active in the WELL for more than fifteen years. But when the word got around in 2010 that I had been diagnosed with cancer (I'm healthy now), people from the WELL joined my other friends in driving me to my daily radiation treatments. Philcat was one of them. Like many who harbor a special attachment to their home town long after they leave for the wider world, I've continued to take an interest - at a distance - in the place where I learned that strangers connected only through words on computer screens could legitimately be called a "community."

I got the word that the WELL was for sale via Twitter, which seemed either ironic or appropriate, or both. Salon, which has owned the WELL since 1999, has put the database of conversations, the list of subscribers, and the domain name on the market, I learned.

I was part of the WELL almost from the very beginning. The Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link was founded in the spring of 1985 - before Mark Zuckerberg's first birthday. I joined in August of that first year.

I can't remember how many WELL parties, chili cook-offs, trips to the circus, and other events - somewhat repellingly called "fleshmeets" at the time - I attended. My baby daughter and my 80-year-old mother joined me on many of those occasions. I danced at three weddings of WELLbeings, as we called ourselves, attended four funerals, brought food and companionship to the bedside of a dying WELLbeing on one occasion. WELL people babysat for my daughter, and I watched their children.

Don't tell me that "real communities" can't happen online.

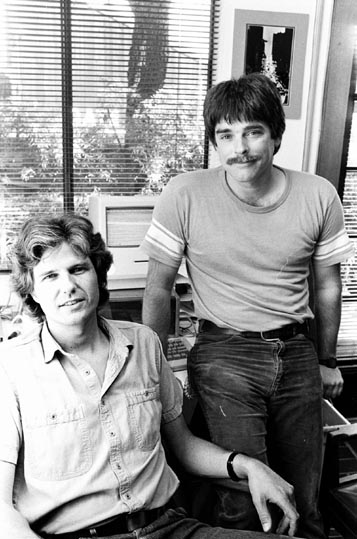

In the early 1980s, I had messed around with BBSs, CompuServe, and the Source for a couple of years, but the WELL, founded by Stewart Brand of Whole Earth Catalog fame and Larry Brilliant (who more recently was the first director of Google's philanthropic arm, Google.org), was a whole new level of online socializing. The text-only and often maddeningly slow-to-load conversations included a collection of people who were more diverse than the computer enthusiasts, engineers, and college students to be found on Usenet or in MUDs: the hackers (when "hacking" meant creative programming rather than online breaking and entering), political activists, journalists, actual females, educators, a few people who weren't white and middle class.

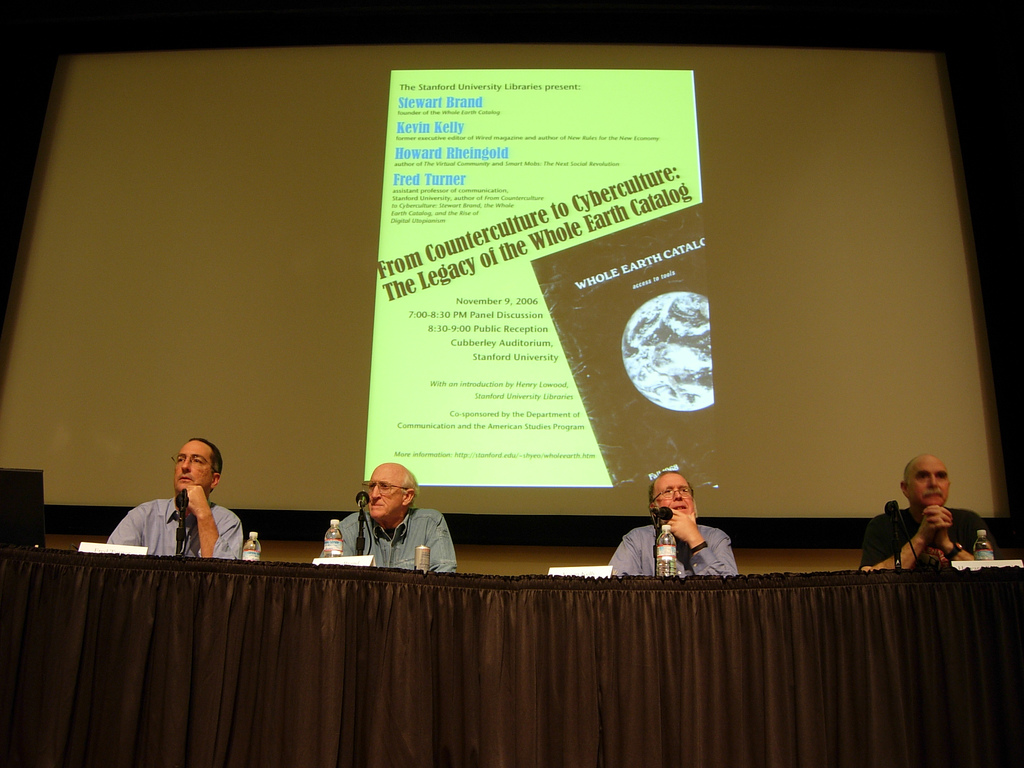

PLATO, Usenet, and BBSs all pre-dated the WELL. But what happened in this one particular online enclave in the 1980s had repercussions we would hardly have dreamed of when we started mixing online and face-to-face lives at WELL gatherings. Steve Case lurked on the WELL before he founded AOL and so did Craig Newmark, a decade before he started Craigslist. Wired did a cover story about "The Epic Saga of the WELL" by New York Times reporter Katie Hafner in 1995 (expanded into a book in 2001), and in 2006, Stanford's Fred Turner published From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism which traced the roots of much of today's Web culture to the experiments we performed in the WELL more than a quarter century ago. The WELL was also the subject of my Whole Earth Review article that apparently put the term "virtual community" in the public vocabulary and a key chapter in my 1993 book, The Virtual Community.

Yet despite the historic importance of the WELL, I've grown accustomed to an online population in which the overwhelming majority of Facebook users have no idea that a thriving online culture existed in the 1980s.

In 1994, the WELL was purchased from owners the Point Foundation (the successor to the Whole Earth organization) and NETI, Larry Brilliant's defunct computer conferencing software business. The buyer, Rockport shoe heir Bruce Katz, was well-meaning. He upgraded all the infrastructure and hired a staff. But his intention to franchise the WELL didn't meet with the warmest reception from the WELL community. Let's just say that there was a communication mismatch between the community and the new owner.

Panicked that our beloved cyber-home was going to mutate into McWell, a group of WELLbeings organized to form The River, which was going to be the business and technical infrastructure for a user-owned version of the WELL. Since the people who talk to each other online are both the customers and the producers of the WELL's product, a co-op seemed the way to go. But the panic of 1994 exacerbated existing animosities - hey, it isn't a community without feudin' and fightin'! - and the River turned into an endless shareholders meeting that never achieved a critical mass. Katz sold the WELL to Salon. Why and how Salon kept the WELL alive but didn't grow it is another story. After the founders and Katz, Salon was the third benevolent absentee landlord since its founding. It's healthy for the WELLbeings who remain - it looks like around a thousand check in regularly, a couple of hundred more highly active users, and a few dozen in the conversation about buying the WELL - to finally figure out how to fly this thing on their own.

In 1985, it cost a quarter of a million dollars for the hardware (a Vax 11/750, with less memory than today's smartphones), and required a closet full of telephone lines and modems. Today, the software that structures WELL discussions resides in the cloud and expenses for running the community infrastructure include a bookkeeper, a system administrator, and a support person. It appears that WELL discussions of the WELL's future today are far less contentious and meta than they were fifteen years ago. A trusted old-timer - one of the people who drove me to cancer treatments - is handling negotiations with Salon. Many, many people have pledged $1000 and more - several have pledged $5000 and $10,000 - toward the purchase.

The WELL has never been an entirely mellow place. It's possible to get thrown out for being obnoxious, but only after weeks of "thrash," as WELLbeings call long, drawn-out, repetitive, and often nasty meta-conversations about how to go about deciding how to make decisions. As a consequence of a lack of marketing budget, of the proliferation of so many other places to socialize online, and (in my opinion) as a consequence of this tolerance for free speech at the price of civility (which I would never want the WELL to excise; it's part of what makes the WELL the WELL), the growth of the WELL population topped out at around 5000 at its height in the mid-1990s. It's been declining ever since. If modest growth of new people becomes economically necessary, perhaps the atmosphere will change. In any case, I have little doubt that the WELL community will survive in some form. Once they achieve a critical mass, and once they survive for twenty-five odd years, virtual communities can be harder to kill than you'd think.

Recent years have seen critical books and media commentary on our alienating fascinatiion with texting, social media, and mediated socializing in general. University of Toronto sociologist Barry Wellman calls this "the community question," and conducted empirical research that demonstrated how people indeed can find "sociability, social support, and social capital" in online social networks as well as geographic neighborhoods. With so much armchair psychologizing tut-tutting our social media habits these days, empirical evidence is a welcome addition to this important dialogue about sociality and technology. But neither Philcat nor I need experimental evidence to prove that the beating heart of community can thrive among people connected by keyboards and screens as well as those conducted over back fences and neighborhood encounters.